FREE SHIPPING IN THE U.S.

In 1983, I returned to New York to make art again after living in Jamaica with Bob Marley. At that point, I had played in Marley’s band and produced Peter Tosh’s first solo album, Legalize It. My photograph of Peter smoking his pipe in an herb field had become the iconic album cover.

Over the years, a few of my closest friends from college had grown from small-time dealers to becoming the largest cannabis smugglers in North America, bringing twenty tons from Thailand on tankers every six months. Half-joking while we were recording the Legalize It album, they used to say to me that if our outcry were successful, it would put them out of business.

I had a devout Jamaican Rasta friend living in New York. He had massive dreadlocks and twenty-seven kids, a deceased wife, and two very much alive ones. He had had a crossover reggae/dance-pop hit in the US and used his royalties to buy a large, rundown house for himself, his wives, and all his kids in a tough neighborhood-Brooklyn’s Bushwick-and to open speakeasies selling the good herb, mainly in nickel bags to the local community. Maybe because I am “white” and involved with Jamaican music, he asked me, “Jaff-I, I know ya have de connections, mon. Set I up, mon. I need da supply of da bess herb. I know ya di right mon can set I up wit da bess, mos reliable resources…”

He was not wholly incorrect in his observation. However, my herb connection was not through Jamaica, but rather the close ties to my college friends-prolific smugglers.

After nearly a decade devoted to music, I was eager to concentrate on making paintings and sculpture and to open a new studio in downtown Manhattan-then the center of the Western art world.

Needing cash to finance my new SoHo studio and begin creating the large-scale works I had envisioned, two times a month a van would show up-courtesy of my college buddies-with twenty or so cardboard boxes, each containing ten-to-fifteen-pound bales of grade A Thai herb sealed in plastic. The best herb you could get at the time. My Rasta friend in Brooklyn would send two of his older kids to start collecting the herb from me, and a week later, they would bring me bags of money, filled mostly with five-dollar bills. My friends would not accept them as legal tender, leaving me the arduous task of devising ways to change tens of thousands of fives into twenties and larger bills.

One day, while separating the bills and extracting the fives, I came across an anomaly and was astonished by the ingenuity of what I was seeing. A counterfeiter had brilliantly turned a one-dollar bill into a five-dollar bill, making sense (sight) overcome essence.

Slowly, while examining the bill, I realized how he had cleverly done it. He had meticulously ripped one corner off four five-dollar bills and Scotch-taped them to the corners of a single one-dollar bill. Being that each five-dollar bill was missing just one small corner, they could still pass as legitimate. The newly created five-dollar bill was a masterful and engaging unique object with a fate of its own.

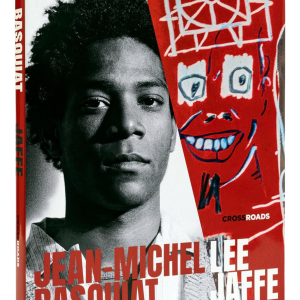

My doorbell rang. Jean-Michel was coming by. We had recently returned from our trip around the world, and would regularly stop by each other’s studios, only a few short blocks apart. I showed him my newly found object. I lit a spliff culled from the Thai bounty and passed it to him. He took a long draw, and the exhaled smoke floated around his eyes and danced towards the ceiling. “I’m going to Andy’s today. Why don’t I get him to sign it, and you can photograph it, and we can blow it up.”